Back when I was still studying architecture, the idea of the panopticon was very intriguing to me. At the time, architecture was for me the aesthetic design of buildings, concerned with making beautiful buildings and nothing more. The idea that architecture could manipulate space to create suppression and power was something that I had not realized possible until my introduction to the panopticon.

Since then, I had been fascinated by the theoretical concept of the panopticon and read extensively about the subject, both in its physical adaptation in Victorian prison designs as well as its theoretical implications on space and power. So while in Dublin, I was excited to pay a visit to Kilmainham Gaol, part of which was constructed with the principles of Bentham’s panopticon.

As we walked through the jail, led by a guide who was obviously enthusiastic about the subject at hand, the architecture slowly took a step back towards the importance of the place. The very first room we were led into, the gaol chapel, looked ordinary and was obviously designed with function in mind. Though as soon as the guide informed us of a man named Joseph Plunkett and his marriage here to his fiancé, just 7 hours before his execution for his involvement in the Easter Rising of 1916, it became apparent that this was not any ordinary prison.

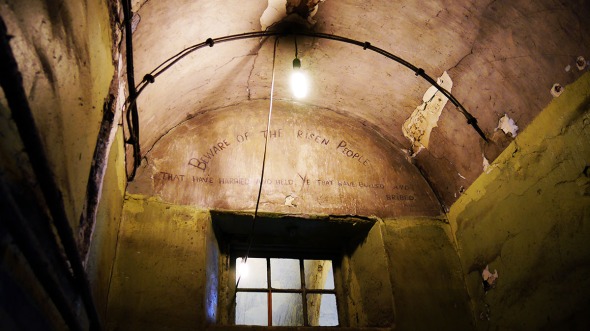

The guide moved us along the building, showing us the cells of various members of the Easter Rising as well as those from earlier Irish rebellions against British rule. Graffiti on the walls along the passageways talked of a rising people and the hopes each rebellion had for a free Irish state.

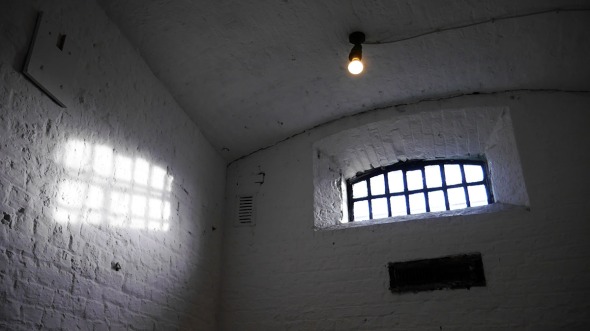

Not even when entering the East Hall, based on the design of the panopticon, managed to shake that feeling of sentiment away. Here, we were introduced to the cell of Éamon de Valera, future President of Ireland, as well as the cell of Grace Gifford, otherwise known as Mrs. Joseph Plunkett. For me, the design of the prison could not match the ambitions and longing of an Irish state for which the political prisoners represent.

All this culminated at the courtyard of Kilmainham Gaol, where two black crosses marked places at opposite ends. One cross represented the place where leaders of the Easter Rising were executed by firing squad, each man having had his chest above his heart pinned with a piece of white cloth to symbolise the target. As for the other cross, that was where James Connolly was shot. His place of execution is offset from the others due to his injury sustained during the Easter Rising, resulting in him being placed in a chair at the other end of the courtyard and shot as he sat tied in his chair.

Perhaps no other building embodies the sentiment of the Irish independence as much as Kilmainham. It was here that those who failed to rebel against the British were held and many executed, and it was here where their courage and suffering inspired the public for independence. Kilmainham was where these visionaries for the Irish Republic were transformed into martyrs, and so became a place of memory and memorial.

In our study of architecture, it is easy to forget the day-to-day occupants of the buildings, all of which write stories within its walls irrespective of the architect’s intention. The panopticon is an exemplar case of surveillance and suppression, yet it is also a monument to the Irish will of independence. As architects, while it is important to consider the theoretical and conceptual implications of the design and its contextual influence, it must also be remembered that buildings can also be places of sentiment.